I am a casual participant in the Great Meridian Bake Along. I don't have time to do every challenge, but this week's challenge was "A Period Bake in a Period Tablescape" and I have one day left of vacation. Since I collect (hoard?) reproductions of 16th century Italian tableware and linens and have a shelf of historical cookbooks, everything seemed serendipitous.

My recipe was marzipanned tourte (VI 120) from Scappi's Opera1 using a loose web redaction2 I've had forever. The recipe is from Book VI of the Opera: Dishes for the Sick and Convalescent. I admit to being a bit lazy on doing my own redactions -the fun for me is in the cooking and eating of historical recipes rather than puzzling out the redaction.

The dough mentioned in VI 120 was "a sheet of pastry as above"1. VI 118 is the recipe that actually has the dough: "...made of fine flour, egg yolks, butter, salt, sugar, and rosewater." I used Stirler's redaction for the amounts of each ingredient and the dough came together easily. My only change was that I had a bottle of rose-almond water already open so I used that rather than pure rosewater. Since the filling included almond paste, I thought it was a reasonable substitute.

The almond paste in Scully's translation is: "get a pound of shelled almonds and grind them thoroughly in a mortar. Have a pound of melted sugar boiling in a casserole pot and put the almonds in it until they become a paste. Put it back in the mortar and grind it up again.

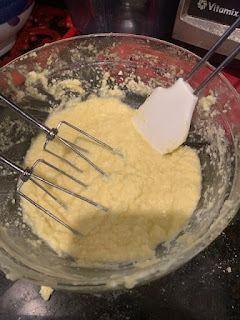

Stirler's almond paste calls for 2 ounces ground almonds, 3 ounces sugar, 1 egg and one ounce of butter. I used almond flour since it is essentially ground almonds. The end product was loose and despite extensive beating, lumpy. But since it was going to be filling, I didn't worry about the lumps (too much).

The next part is where Scully and Stirler really diverge. Per Scully: "when it (the almond paste) has cooled, add in six egg whites and a beaker of milk made from melon seeds." The "milk made from melon seeds" threw me and I didn't want to get derailed researching it, so I ran with Stiler's redaction for this part. In retrospect, I suspect almond milk might have worked. I'm pondering marzipan for Baroness Isabetta's Vigil table next month, so I may go back and revisit Scully's translation soon.

Stirler mixes the almond paste with: "1/2 c pastry cream or 1 vanilla pudding snack cup or 4 oz of cream cheese or 1/2 c ricotta cheese."2 I shuddered at the thought of using a vanilla pudding cup and went with ricotta cheese.

Hmmm... am I going to have enough filling?

Stirler and Scully also diverged on what to do with the filling. Scully says put it a torte pan lined with a sheet of dough. Stirler says to cut the dough into 24 rounds. Since it was more in line with Scully, who translated from the original Italian, my plan was to make a single torte. However, since I did not have enough filling for a torte or ingredients to make a second batch of filling, rounds it was going to be! From this point on, I would be following Stirler's redaction.

But is this enough dough for 24 rounds?

Rolling to 1/16th of an inch got me eleven 4" rounds in the first rollout. Rolling out the leftovers 2 more times, I ended up with a total of 16 rounds. Stirler said 24 rounds but I don't see any way for that to happen. 1/16th of an inch is the absolute thinnest I could roll the dough and rounds smaller than 4" would be really difficult to work with.

Leftover dough after sixteen rounds

I used a teaspoon to fill each round and then folded it over, sealed it with water and cut slits in the top in a vaguely decorative pattern.

I baked them at 420 degrees for 13 minutes, then brushed them with an egg glaze and put them back in for 5 minutes, as per Stirler. If I make these again, I think I'd keep them in a few minutes less. They weren't burnt, but they were a bit browner than I wanted.

I think my oven may be a bit hotter than Stirler's

The finished pastries were slightly sweet but rather bland -I can see why Scappi included them in the cooking for convalescent section. I think they needed more filling, but even just using the teaspoon I did, it threatened to ooze out the sides. And larger rounds would increase the amount of pastry not just the room for filling.

But now that I had my pastries baked, onto part two of the challenge: the table setting.

Table settings are my joy. I have large quantities of photos of extant silver, glassware, ceramics and linens from museum trips and portraits- it's a long term casual research project. I love creating a historically accurate table for when we sit feast or I do a hospitality or vigil table. And I enjoy seeing how I can up my game. (Or perhaps I just can't resist adding to my collection *blush*)

So I had plenty of props to play with....plenty of props.

The tableware cabinet

The table linens collection

Since my focus is third quarter of the 16th century in Venice (and Constantinople) my mind went immediately to still life or "Natura Morta" (dead nature) paintings, as the Italians called them. Dutch still lifes are what most people think of when they hear "still life painting," but Italy also produced notable still life painters, including Caravaggio.4

Still Life with Fruit and Carafe

c1610-20

Pensionante del Saraceni

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Accession Number 1939.1.159

c1625-30

Georg Flegel

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Accession Number 21.152.1

Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge

c 1601-10

Caravaggio (attributed)

Private Collection

While the seventeenth century was the golden age of still life paintings, still life motifs can be seen in 15th century & 16th century art3, so I decided to set the table as a Natura Morta display.

I spent the afternoon and evening rummaging around in my dishes and linens to find the best options, then taking dozens of pictures, in daylight and various types of artificial lighting, and endlessly moving things a fraction of an inch this way and that. Oh and keeping the cats from interfering too much.

Sam, you are not as helpful as you think you are

Until I found the composition I was happy with.

It was actually a lovely way to spend my last day of winter vacation.

--------------------

Scully, Terence trans. The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570). Torento: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

Stirler, Gael. "Three Recipes from The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570)" https://stores.renstore.com/food-and-drink/renaissance-treats#.Vy1Msr5Ggqg Accessed 3 January 2022.

Liedtke, Walter. "Still Life Painting in Northern Europe: 1600-1800" Metropolitan Museum of Art Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nstl/hd_nstl.htm Accessed 3 January 2022.

--- . "The Origins of Still Life in Italy" https://galleriaborghese.beniculturali.it/en/exhibition/lorigine-della-natura-morta-in-italia-caravaggio-e-il-maestro-hartford/# Accessed 3 January 2022.