This was a tough challenge to find inspiration for. I had some lovely Renaissance patterned upholstery fabric that I bought last year to use for a 16th century gown, but I knew there was no way that I was going to finish a gown in a month even if I had a bodice pattern that I was happy with (which I didn't). So mid-month, when no more exciting and executable idea had presented itself, I went with plan B: A 16th century Italian saccoccia (pocket). I laughingly swear that the entire reason I wear 16th century Italian and 16th century Ottoman is that pockets were historically accurate.

Saccoccia are seen in various 16th century Italian paintings and here are also several extant Spanish examples, which are very similar to the ones in Italian paintings. Both the Italian and Spanish ones bear a strong resemblance to the 18th century pocket, examples of which are far more commonly found in museums. I have not come across any extant 16th century English examples, however a search on "pockets" at elizabethancostume.net turned up 146 references in wills and wardrobe accounts. However, rather interestingly, the V&A article on the history of pockets starts in the 17th century not the 16th. As does an essay from the Pockets of History collection at the University of Creative Arts. It's an interesting research rabbit hole, but outside the scope of this challenge, so it will have to wait for another time.

Based on the examples I'd found in paintings, the saccoccia appears in the mid 16th century, which was confirmed in Anea's excellent article that I stumbled upon later in my research. Working class women appear to have worn their saccoccia tied on over their gowns; upper class women most commonly wore theirs under their gown and accessed it through a slit in the skirt.

Even working class women could have saccoccia made of patterned fabrics and trimmed elaborately.

The fabric definitely qualified as patterned. It was some upholstery fabric of unknown man-made fibers. I was initially reluctantly to use the fabric before I actually created the gown, but needs must if I was going to complete the challenge. In retrospect, I'm glad I did, because this stuff frays like @#$% and was annoying enough to work with, that I will probably end up donating the rest of the bolt to a SCA rummage sale. Life is too short to work with fabric that behaves that badly.

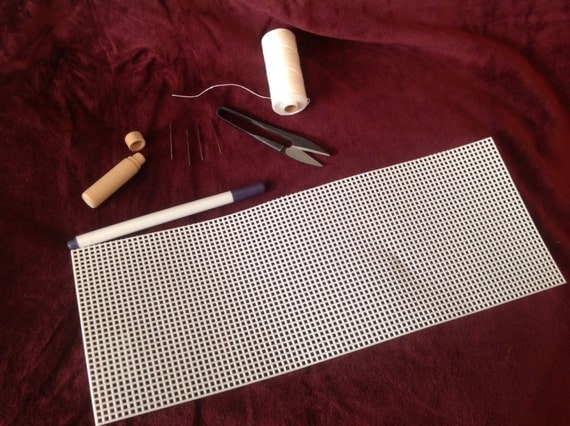

The pattern was easily enough drafted up and cut out.

I had some deep claret silk scraps in my scrap bin that were perfect for a lining and I was cooking with gas. I was going to finish this challenge on time if not early! <insert ominous music> Then the fabric started fraying like there was no tomorrow and I threw the wretched thing in my sewing basket for a probably permanent time out and decided maybe I just wasn't going to do challenge #8.

I'd asked my dear friend, Mistress Alessandra, to make me some teal cotton petersham for the waist tie and while I was over at her house for a sewing day, the subject of the saccoccia came up. She solved the problem handily enough by cutting off a chunk of the leftover she had from weaving my petersham up and said "bind the opening." This is probably why she is the laurel and I am the student. :)

Not long after, I had a finished saccoccia.

The Challenge: #8 Patterns

Material: 1/4 yard upholstery fabric, scraps of silk for lining

Year: later 16th century

Notions: Silk thread, cotton petersham

Pattern: Self drafted based on the examples in paintings

How historically accurate is it? The fabric is man-made fiber. Its hard to feel good about historical accuracy after that. But the silk thread and hand woven cotton petersham are both plausible for the 16th century. (Italy had had a cotton industry for several centuries at that point)

Hours to complete: 3-4 maybe

First worn: Not yet. It's still too warm to wear Italian.

Total cost: $20 for the cotton petersham. Everything else was from the stash,

_______________________________________________

1 I originally found this picture on www.modehistorique.com but the location of the drawing was not indicated. Upon googling for the image, which is often helpful in establishing provenance, every hit seemed to lead back to either modehistorique or different Allori. This is, in my experience, a red flag on validity of the source. Based on what I have seen of Allori's work, it doesn't seem implausible for it to be an Allori sketch, but I will feel easier when I can locate exactly what and where it is located.

References

Anea. "A Renaissance Saccoccia." The Anea Costumes. np. 2016. Web. 15 September 2016. <http://elizabethancostume.net/cyte/search/node/pockets%20synonym%3A1%20>

Anea. "16th century Italy + loose pockets" Anea Costumes: Fashion and Design Past and Present. np. 2016. Web. 15 September 2016. "http://aneacostumes.tumblr.com/post/132201315761/16th-century-italy-loose-pockets-loose-pockets"

Burman, Barbara and Seth Denbo. "A History of Pockets" Visual Arts Data Service Pockets of History Collection. Surrey, 2016. Web. 11 September, 2016. <http://www.vads.ac.uk/texts/POCKETS/history_of_tie-on_pockets.pdf>

Leed, Drea. Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Uploaded. The Elizabethan Costuming Page. Dayton, Ohio 2010. Web. 14 September 2016. <http://elizabethancostume.net/cyte/search/node/pockets%20synonym%3A1%20>

Lorraine, Sarah. "I'm Done?" Mode Historique. San Jose, CA 2016. Web. 1 September 2016. <http://elizabethancostume.net/cyte/search/node/pockets%20synonym%3A1%20>

--- "A History of Pockets" Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2016. Web. 11 September, 2016. <http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/history-of-pockets/>

---. Faltriquera 1575-1600. Museo del Traje Online Collection, Madrid, Spain 2016. Web. 15 September 2016. <http://museodeltraje.mcu.es/index.jsp?ruta=4%2C17%2C48&referencia=MT00790&id=48>

Saccoccia are seen in various 16th century Italian paintings and here are also several extant Spanish examples, which are very similar to the ones in Italian paintings. Both the Italian and Spanish ones bear a strong resemblance to the 18th century pocket, examples of which are far more commonly found in museums. I have not come across any extant 16th century English examples, however a search on "pockets" at elizabethancostume.net turned up 146 references in wills and wardrobe accounts. However, rather interestingly, the V&A article on the history of pockets starts in the 17th century not the 16th. As does an essay from the Pockets of History collection at the University of Creative Arts. It's an interesting research rabbit hole, but outside the scope of this challenge, so it will have to wait for another time.

Based on the examples I'd found in paintings, the saccoccia appears in the mid 16th century, which was confirmed in Anea's excellent article that I stumbled upon later in my research. Working class women appear to have worn their saccoccia tied on over their gowns; upper class women most commonly wore theirs under their gown and accessed it through a slit in the skirt.

Study of a Woman with a Tray

Alessandro Allori

c. 1570-80

Provenance Unknown by me1

Detail from "Women at her toilet"

Allessandro Allori

c. 1575-78

fresco in Gaddi Chapel

Church of Santa Maria Novella,

Florence, Italy

The fabric definitely qualified as patterned. It was some upholstery fabric of unknown man-made fibers. I was initially reluctantly to use the fabric before I actually created the gown, but needs must if I was going to complete the challenge. In retrospect, I'm glad I did, because this stuff frays like @#$% and was annoying enough to work with, that I will probably end up donating the rest of the bolt to a SCA rummage sale. Life is too short to work with fabric that behaves that badly.

The pattern was easily enough drafted up and cut out.

I had some deep claret silk scraps in my scrap bin that were perfect for a lining and I was cooking with gas. I was going to finish this challenge on time if not early! <insert ominous music> Then the fabric started fraying like there was no tomorrow and I threw the wretched thing in my sewing basket for a probably permanent time out and decided maybe I just wasn't going to do challenge #8.

I'd asked my dear friend, Mistress Alessandra, to make me some teal cotton petersham for the waist tie and while I was over at her house for a sewing day, the subject of the saccoccia came up. She solved the problem handily enough by cutting off a chunk of the leftover she had from weaving my petersham up and said "bind the opening." This is probably why she is the laurel and I am the student. :)

Not long after, I had a finished saccoccia.

The Challenge: #8 Patterns

Material: 1/4 yard upholstery fabric, scraps of silk for lining

Year: later 16th century

Notions: Silk thread, cotton petersham

Pattern: Self drafted based on the examples in paintings

How historically accurate is it? The fabric is man-made fiber. Its hard to feel good about historical accuracy after that. But the silk thread and hand woven cotton petersham are both plausible for the 16th century. (Italy had had a cotton industry for several centuries at that point)

Hours to complete: 3-4 maybe

First worn: Not yet. It's still too warm to wear Italian.

Total cost: $20 for the cotton petersham. Everything else was from the stash,

_______________________________________________

1 I originally found this picture on www.modehistorique.com but the location of the drawing was not indicated. Upon googling for the image, which is often helpful in establishing provenance, every hit seemed to lead back to either modehistorique or different Allori. This is, in my experience, a red flag on validity of the source. Based on what I have seen of Allori's work, it doesn't seem implausible for it to be an Allori sketch, but I will feel easier when I can locate exactly what and where it is located.

References

Anea. "A Renaissance Saccoccia." The Anea Costumes. np. 2016. Web. 15 September 2016. <http://elizabethancostume.net/cyte/search/node/pockets%20synonym%3A1%20>

Anea. "16th century Italy + loose pockets" Anea Costumes: Fashion and Design Past and Present. np. 2016. Web. 15 September 2016. "http://aneacostumes.tumblr.com/post/132201315761/16th-century-italy-loose-pockets-loose-pockets"

Burman, Barbara and Seth Denbo. "A History of Pockets" Visual Arts Data Service Pockets of History Collection. Surrey, 2016. Web. 11 September, 2016. <http://www.vads.ac.uk/texts/POCKETS/history_of_tie-on_pockets.pdf>

Leed, Drea. Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Uploaded. The Elizabethan Costuming Page. Dayton, Ohio 2010. Web. 14 September 2016. <http://elizabethancostume.net/cyte/search/node/pockets%20synonym%3A1%20>

Lorraine, Sarah. "I'm Done?" Mode Historique. San Jose, CA 2016. Web. 1 September 2016. <http://elizabethancostume.net/cyte/search/node/pockets%20synonym%3A1%20>

--- "A History of Pockets" Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2016. Web. 11 September, 2016. <http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/history-of-pockets/>

---. Faltriquera 1575-1600. Museo del Traje Online Collection, Madrid, Spain 2016. Web. 15 September 2016. <http://museodeltraje.mcu.es/index.jsp?ruta=4%2C17%2C48&referencia=MT00790&id=48>